When Miles Shanor told their high school English teacher they wanted to follow in his footsteps, he did everything in his power to warn them away.

“He spent the better part of an hour trying to convince me not to do it…,” Shanor said, “…not to go into education because there was no money in it. This guy did not have any respect for himself and his profession.”

Shanor said it was a symptom of a problem sweeping education these days: that thanks to conditions of low pay and resource-starved classrooms, professionalism has left the profession.

However, they said they’re still determined to be an English teacher, because of how much it meant to them to have teachers stand up for them in high school — and the joys of getting to rant about one of their favorite subjects all day, they added.

But, like with many education majors, one glaring thing stands in the way: in order to finish their degree, Shanor will have to spend a semester working forty hours a week in a classroom — plus prep time and community outreach — for free.

In fact, they and many other education majors have to pay to work in classrooms. Student teaching is counted at the University of Nevada, Reno as a seminar credit, for which regular tuition and fees apply. Shanor added that education majors are also discouraged from seeking additional paid work while teaching, or looking for student teaching placements that could be paid.

“I’ve been told by some of my former coworkers who graduated with the same degree that I have to already start saving for student teaching,” Shanor said. “It cost them money, and they were not sustainably living if you can even call it that.”

Members of the University of Nevada Education Association at the NEA Aspiring Educators Conference this past summer. Miles Shanor (left) is working to become an English teacher.

But Shanor also serves as president of the University of Nevada Education Association, the university’s member chapter of the National Education Association, a teacher’s union. Shanor and their fellow officers are optimistic that the situation around student teaching can change.

Kasandra Medina-Torres, the club’s historian, said Nevada is part of a huge nationwide push from the NEA to get student teachers paid for their work — and that it’s the first step towards repairing the conditions that push teachers out of classrooms and create shortages in the first place.

“There’s a huge issue with teacher shortages right now,” Medina-Torres said. “Some of the big reasons are burnout, low pay, a lot of challenging behaviors in the classroom and not enough resources to help manage those behaviors. That is pushing a lot of current educators out of the profession.”

But if new teachers come into the profession feeling supported, she said, they’re less likely to burn out running on fumes, and leave.

“It puts a little more of that professionalism back into the profession,” Medina-Torres said. “When you go into your first year of teaching, you’re not just set up for failure. You have experience now, and it’s paid experience that you were valued for.”

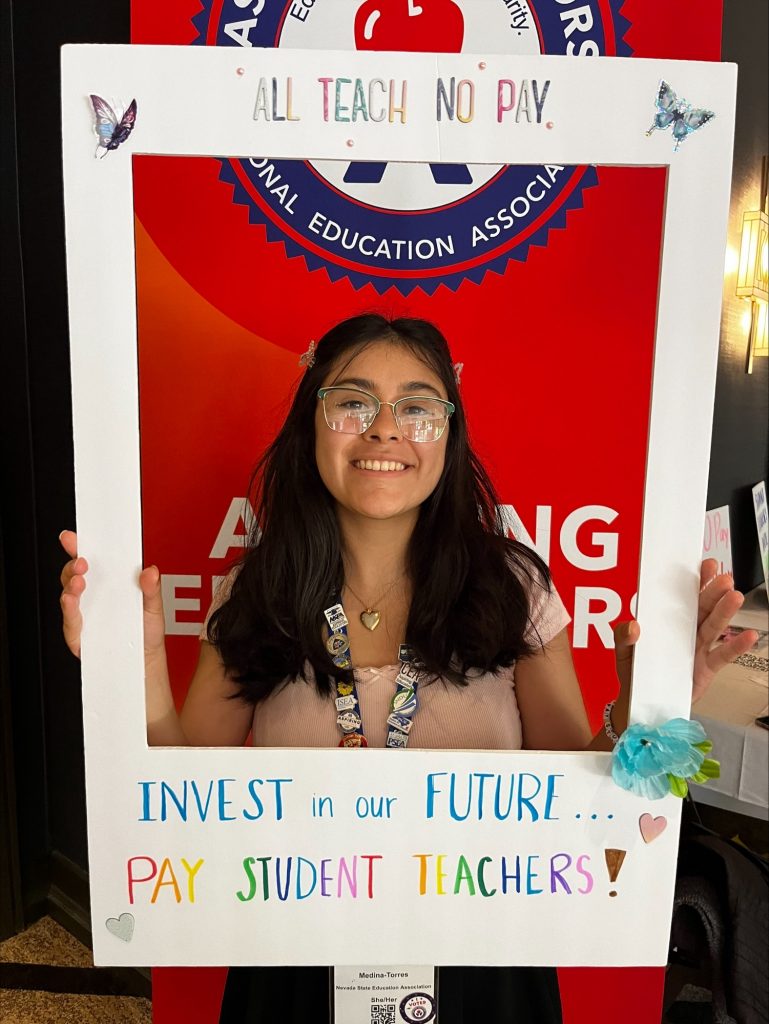

Kasandra Medina-Torres poses for a photo at the NEA Aspiring Educators Conference this summer. Torres hopes to teach at the elementary school level.

Otherwise, added Jordan Eddington, an elementary education major with an emphasis in early childhood education and secretary/treasurer of the club, would-be teachers leave the profession before they even begin.

“A lot of what deters education majors is being told that your whole last semester you can’t work [another job] and you’re not getting paid for anything you’re doing,” Eddington said. “We have a friend who dropped out because of it and just did a history major instead of both [history and education].”

Medina-Torres added that the club is still in conversation with the Nevada State Education Association, the state’s member chapter, about what the program would look like. One idea is a residency-style approach that would keep new teachers in the state for a period after their first paid year of student teaching.

The Nevada State Education Association did not respond to requests for comment about the specifics and funding of such a program.

With the 2025 session of the Nevada Legislature on the horizon, the University of Nevada Education Association is hoping to lobby lawmakers in support of aspiring educators who they believe deserve to get paid, however the program might eventually look. The club is hoping to raise the issue’s profile in the meantime, with events, public speakers and an online push.

Until then, Medina-Torres said, she’ll do her best to make it work.

“Not being paid means I have to look for a job while I’m student teaching as well,” Medina-Torres said. “Which means I’m not able to focus all my attention on student teaching and learning — which then feeds into that burnout that a lot of us are experiencing, and we’re not even teachers yet.”

Peregrine Hart can be reached via email at peregrineh@unr.edu or on Instagram via @pintofperegrine.