A few years ago, Forrest and Nadine Fasig went hiking in the Pilot Mountains, near Mina, Nevada. They ventured to the area in search of coral fossils, but they stumbled upon something entirely different protruding from one of the area’s hills.

Soon after, they sent a picture of it in an email to University of Nevada, Reno paleontologist Dr. Paula Noble.

“They took a picture of it and sent it to my advisor [Noble] like, ‘is this what I think it is?’ And she was like ‘yes, it is! Where did you find it?” Gary McGaughey, a geology masters’ student studying the site fossils, said.

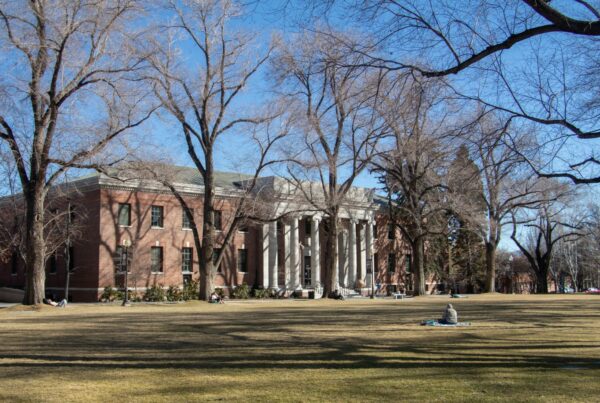

The following summer, a research team from the University of Nevada, Reno, the University of Utah, Vanderbilt University and the University of Edinburgh investigated the site. McGaughey, who was in the market for a thesis topic, found himself in luck.

The Fasigs found a bone. A piece of backbone, to be exact. It belonged to a massive ichthyosaur that roamed the seas during the late Triassic era, Shonisaurus popularis. The Triassic dates from 252 million years ago to 201 million years ago. With the Fasigs’ continued help on the project, it would later lead to another site, with another fossil, belonging to the most recent specimen of its family ever found.

“When I saw these very large ribs sticking out of the hillside, there was no doubt as to what they were. I probably smiled for two hours or something,” McGaughey said.

Ichthyosaurs, McGaughey explained, “are a marine reptile that showed up at the very beginning of the age of the dinosaurs: they actually show up before the first dinosaurs.” Originally descended from land-dwelling reptiles, their body adapted to the oceans with time.

“They were originally somewhat lizard-like, but they got less and less lizard-like as time went on,” McGaughey said. “By the beginning of the Jurassic, they looked really dolphin-like.”

McGaughey is focusing on another member of the Shastasaurid family, which includes Shonisaurus popularis, the species of the Fasigs’ initial find and Nevada’s official state fossil. Members of this family of marine predators were the largest of the ichthyosaurs, with the longest specimen ever found landing at an estimated 21 meters.

But one lingering area of uncertainty is entangled with the mass extinction that wiped out a huge swath of land and marine life at the end of the Triassic, about 201 million years ago.

“Basically, these large ichthyosaurs in Nevada seemed to go away at a point in the middle of the Late Triassic,” McGaughey said. “We have a record of them up until this point, and then the rock changes types, and we don’t see them after that.”

Some 19 million years after we lose the ichthyosaurs in the rock record, the End-Triassic extinction announces itself with widespread volcanic rock deposits and chemical markers, right where a number of other species disappear. The question of when the Shastasaurid extinction lands is what interested McGaughey: did these marine reptiles die off before the big extinction killed everything else? Or did they last all the way up until the Triassic period’s deathly end?

To answer this question, McGaughey’s thesis goes deep on trying to give the semi-articulated ichthyosaur skeleton, affectionately known as “Costa Monstrum” (rib monster) an age.There isn’t any material available to use radio-isotope dating on the fossil directly, so the team has relied on two methods: biostratigraphy and geochemistry.

In biostratigraphy, paleontologists use other nearby fossils whose ages they already know. The gold standard for biostratigraphic dating in the age of the dinosaurs is a fossil of an extinct shellfish with a passing resemblance to the modern-day nautilus: the ammonite.

“There are a lot of ammonites in this area. They’re pretty well known,” McGaughey said. “We found ammonites all around our bone layer, so it was exciting to be like, ‘ah, yes, this is a significant ammonite for me to date this ichthyosaur!'”

The site’s geochemistry allowed another research team to date some layers of volcanic ash around the ichthyosaur, while McGaughey’s team used a distinct chemical sign of extensive volcanic activity to pinpoint the End-Triassic at the site.

“We took a bunch of samples at 10-centimeter intervals, and then we ran those for their carbon. What shows up is this weird spike: a negative carbon isotope excursion,” McGaughey said. “This seems to correlate with a large volcanic eruption. We used that to kind of position us relative to this extinction.”

The completed thesis is still some time away, but McGaughey feels pretty firm in his conclusions.

“The biggest thing that we can say with a lot of confidence now is that these large ichthyosaurs survived until this End-Triassic extinction,” he added. “We’re within 1.5 meters [in the rock], which is very close in geological terms, probably within a couple hundred thousand years, which I know seems like a lot, but for geologists, that’s a rounding error, almost.”

In addition to helping us better understand the Shastasaurids and their relationship to the End-Triassic extinction, McGaughey is hopeful that this skeleton will yield yet more secrets as the excavation team gets more of it out of the ground.

“It could be years of work, or the next time we go out there, it could just end,” he said. “We have this roaring potential of what we could find out there compared with what we currently have.”

Peregrine Hart can be reached via email at edrewes@sagebrush.unr.edu or via Twitter @EmersonDrewes.