The McKinley Arts & Culture Center on the Truckee River plays host to the offices of several Reno arts organizations. Through Feb. 10, it housed the work of three Truckee Meadows Community College students from one of their art courses, a portfolio class required for the completion of a fine arts associate’s degree.

Exhibitions are a promising source of new artists whose work might take us all by storm in the coming years. In this case, the three portfolios on display present wildly different visions — yet somehow pair very well.

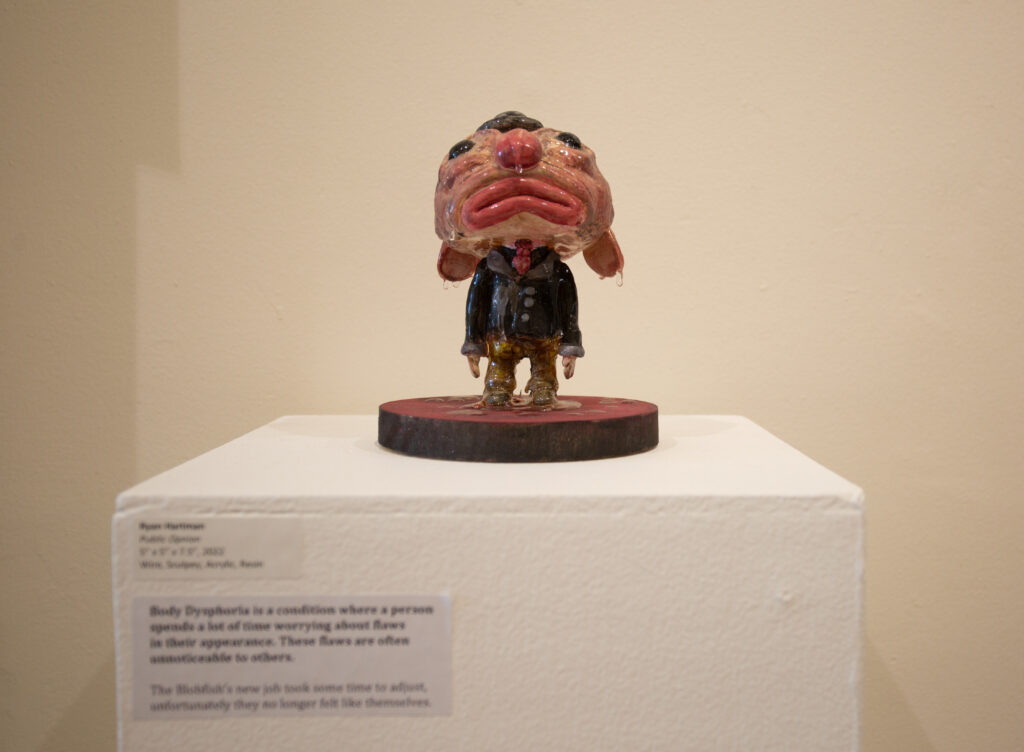

Through sculpture, Ryan Hartman’s “Head Case” warps the experience of the neurodiverse into weird and wonderfully ghoulish figures. However vivid and memorable, though, there are questions to be had about how the material is handled.

Body dysmorphia takes the stage in “Public Opinion”, where a suited, fleshy blobfish gazes shamefully out at the viewer. Hartman’s attention to color and texture make the piece a sobering experience. One might feel almost chastened giving it attention.

“World’s Smartest Goldfish” — a figure also containing creatures hailing from the ocean — speaks to autism. Hartman employs dripping resin to render the sculpture permanently sopping wet. The resin paired with highly expressive faces, is one of the portfolio’s most apt tools for depicting alienation.

What makes “Head Case” linger is Hartman’s talent for slow-building body horror.

Two figures, anxiety’s “Vulnerable Tough Guy” and ADHD’s “Absent Awareness” feature their characters physically falling apart. “Vulnerable Tough Guy” shows a mouse trembling as he loses his fur, and “Absent Awareness” depicts a deer unaware of the antlers beside him on the ground. It takes some slow observation to understand both of these scenes fully, and that’s when Hartman’s perspective is working at its highest power.

Overall, the portfolio achieves an impressive depth of feeling with distinct and well-chosen imagery. However, I’d be remiss not to wonder if it’s really the right approach to show these subjects as only a form of horror.

The real-life experience of carrying any one of these diagnoses is complex. In “Head Case”, the score only carries a few melodies — the loudest of which is a bystander’s vague unease.

Meanwhile, in Margaret Pollock’s “Mort”, a somber use of oil on canvas tackles grief through still life.

Pollock absolutely nails the most delicate of her subjects, from the papery thinness of wilting iris petals in “Irises are a Way for my Father to Remember” to an exquisitely-rendered skull in “Tears with Tea and Myself.” Very little life besides botanicals appears in the portfolio, but when it does, she captures it with the same feathery technique.

Even if the viewer doesn’t catch the theme of grief upon their first viewing, there’s a visual language in the pieces linking all of us to plants, fading and ephemeral. A lot of it is in texture: Pollock’s tactile skill with such a difficult-to-control medium is not to be overstated.

A restrained use of color throughout the portfolio makes it pop in “Stories Told by My Parents”, a large oil on canvas that manages to stay somber while reaching for brighter hues. Rather than using living flowers as a centerpiece, it presents only fallen petals, surrounding an intricate, eye-catching vase completely vacant of whatever it once held.

Looking through the rest of Pollock’s paintings all the life within them is either dead or dying.

Opposite her darker companions, Juliana Horvath’s “Calm Spaces” rounds out the group exhibition with collage.

Horvath doesn’t even begin to grasp a heavy topic. In fact, the portfolio veers closer to a magazine spread, but she does achieve a compelling sense of motion in her landscapes by pairing models with bright scenery and hand-drawn florals.

In a move that adds a delightful degree of fantasy to the portfolio, there are also a few choice fungi. While “Calm Spaces” doesn’t actively try to channel fairies or magic, Horvath’s use of color and her gleeful disregard for real-life scale certainly scratch a subtly magical itch.

Across the wall display, a recurring path in paint weaves from one piece to another, shifting color in a bright but confined palette. It curves and doubles back on itself, in a pattern much like wandering.

A standout, “The Garden Door” is flagrant with detail; an inviting pairing of pink and green. If “Calm Spaces” were a place — and it’s certainly absorbing enough to feel like one — it’s where you’d be invited in.

Peregrine Hart can be reached via email at peregrineh@nevada.unr.edu or on Twitter via @pintofperegrine.